Clinical Characteristics of Infantile Colic

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

To diagnose infantile colic from parent questionnaires, as well as investigating the risk factors and clinical course of infantile colic.

Methods

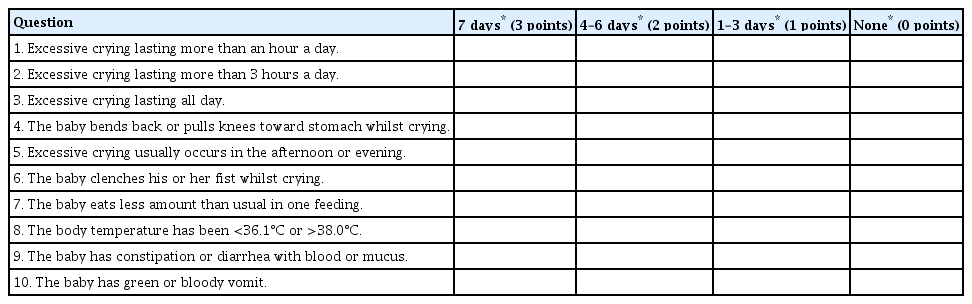

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 462 infants, with a corrected age of <4 months at the time of visiting Inha University Hospital from January to December 2017. Parents responded to a 10-line questionnaire consisting of seven items relating to colic symptoms and three further items relating to underlying disease. The score was based on the number of days each symptom was evident during the preceding week. We defined infantile colic as the sum total being greater than seven points; if at least one of the three symptoms suggesting underlying disease was present, the infant was excluded from the diagnosis.

Results

One hundred and sixty-seven infants (36.1%) satisfied the criteria. The lower the gestational age, the more infantile colic they developed (P<0.001). The prevalence of colic was higher in infants born with a birth weight <2.5 kg (62.7% vs. 24.4%, P<0.001) and in infants small for their gestational age, in the <10th percentile (54.5% vs. 33.7%, P=0.003). The prevalence of colic was significantly different according to the type of feeding (P=0.001), being the lowest in breast-only feeding (29.8%), 32.8% in mixed feeding with breast milk and formula, and 49.7% in formulaonly feeding. Colic symptoms improved by administering hydrolyzed formula (87.5%), low-lactose formula (47.1%), galactosidase (44.4%), and the probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri (34.5%).

Conclusion

The prevalence of infantile colic was over 30%. Prematurity, lower birth weight, and small for gestational age were the risk factors of infantile colic. Clinical improvement was observed when active intervention was performed.

서론

영아 산통은 신체에 특정 질환이 없는데도 영아가 지속적으로 잘 설명되지 않는 과도한 울음을 보이는 증상을 말하며, 생후 6개월 미만의 아기들에서 병원을 찾는 중요한 문제 중의 하나이다. 빠르게는 생후 첫 2–3주에 시작하여 생후 4–6개월까지 지속되다가 호전되는 양상을 보이며, 주로 저녁 시간에 발작적으로 심하게 울며 두 손을 움켜쥐거나 두 다리를 배 위로 끌어당기거나 배에 힘을 잔뜩 쥐고 얼굴을 붉히는 등 심한 보챔이 특징이다[1,2]. Wessel’s criteria에 따르면, 발작적이고 과도한(fussing and excessive) 울음이 적어도 3주 동안, 하루 3시간 이상, 주 3일 이상 지속되는 것을 영아 산통으로 정의한다[3]. 이 기준에 따라 영아 산통을 정의하고 있는 기존 연구들에 따르면 영아 산통의 빈도는 약 9%–20%로 보고된다[2,4]. 그러나 실제는 이보다 높은 빈도로 보호자들은 자신의 아기들이 영아 산통으로 괴로워 한다고 호소하고 있으며, 이는 영아 및 가족 구성원 모두에게 심각한 고통을 안겨주고 있다[5]. 많은 연구 결과에 따르면 영아 산통이 미성숙한 위장관에서 기인하는 기질적인 통증에서 유래한 것으로 추측해 볼 수 있으나[6-11], 아직도 이 질환에 대한 원인이나 위험인자는 불분명하며 치료 또한 분명하지 않은 채 논란이 되고 있다[12].

본 연구에서는 영아 산통의 진단 기준을 좀 더 객관화시키고 점수화하여, 점수에 따른 유병률을 구해보고자 하였으며, 위험인자를 찾아 질환의 원인을 유추해보고 치료에 대해 모색하여 영아 산통에 대한 이해를 높이고자 하였다.

대상 및 방법

2017년 1월부터 12월까지 1년간 인하대병원 외래를 방문한 6개월 미만의 영아 중 외래 방문 시기 당시 연령이 교정 4개월 미만인 462명을 대상으로 후항적 의무기록 리뷰를 진행하였다. 영아 산통의 진료를 목적으로 방문하는 환아 이외에도, 신생아 집중치료실 입원 치료 이후 추적 관찰, 영유아 검진, 예방 접종을 목적으로 방문하는 영아를 대상에 포함하였으며, 총 3회까지의 외래 내원 당시 보호자가 진료를 위해 기록한 설문지, 소아청소년과 전문의가 병력 청취와 진찰을 통해 기록한 외래 의무기록을 조사하였다. 외래에 내원하는 보호자들에게는 아기가 호소하는 증상과 관련된 설문지가 제공되었다. 설문지는 영아 산통에 대해서 연구한 기존 문헌에 실린 영아 산통의 특징적인 임상 양상을 기반으로 하였으며[13-21], 하루 당 총 울음시간(설문 항목 1–3), 증상의 발현 시 아기의 전반적인 상태(설문 항목 4, 6), 증상 발현이 주로 오후나 저녁때에 생기는지(설문 항목 5), 영아 산통이 수유 습관에도 영향을 미치는지(설문 항목 7) 등에 대한 영아 산통 관련 7개 항목과 36.1°C 미만이거나 38.0°C 이상의 체온 이상이나, 혈액이나 점액이 묻어있는 변비나 설사, 녹색 혹은 혈흔이 섞인 구토 등 위중한 기저 질환의 가능성을 배제하기 위한 3개 항목(설문 항목 8–10)으로 구성하였다(Table 1). 보호자가 느끼는 주관적인 판단을 설문지를 통해 점수화하였으며, 점수는 최근 1주일 동안 각 항목의 증상을 호소하는 일수를 기준으로, 각 항목의 증상 발현이 1주일 내내 있을 경우 3점, 4–6일 있을 경우 2점, 1–3일 있을 경우 1점으로 하였고, 영아 산통 7개 항목 점수의 총합이 7점 이상일 경우를 영아 산통으로 정의하였다. 총 462명의 대상자들은 외래에 방문할 때마다 같은 설문지를 제공받았고, 6개월 동안 최대 3회의 방문 중 1회라도 상기 기준을 충족할 경우에는 영아 산통으로 정의하였다. 좀 더 객관적인 진단을 위해 보호자가 작성한 설문지에서 기준을 충족하지 못할 경우라도, 의료진이 작성한 의무 기록을 토대로 영아 산통이라고 진단된 대상도 영아 산통 군으로 포함하였다. 위중한 기저 질환의 가능성을 시사하는 3개 항목에서 1점이라도 점수가 나오는 경우는 영아 산통에서 제외하였다. 또한 설문지의 7개의 각 항목의 합계를 통해 영아 산통 관련 증상 중 빈번하게 호소하는 증상이 무엇인지 분석하였다. 또한 영아 산통의 위험인자와 치료 경과를 확인하기 위해 임신나이, 출생체중, 성별, 수유 종류, 영아 산통으로 인한 분유 변경 여부, 유산균을 포함한 약물 복용에 대한 자료를 수집하였다. 본 연구는 후향적 데이터분석연구로 연구자의 동의서취득이 면제되며, 연구의 계획은 사전에 인하대병원 기관생명윤리위원회의 승인을 받았다(IRB No. 2018-07-001-001).

조사한 자료들은 Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft, San Francisco, CA, USA)에 입력하고, SPSS version 19.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA)을 사용하여 통계적 분석을 시행하였다. 조사된 자료의 값은 빈도(백분율) 또는 중앙값(범위)으로 표기하였고 이산 변수는 chisquare test를 이용하여 분석하였으며, P-value가 0.05 미만인 경우를 통계학적 의의가 있는 것으로 정의하였다.

결과

1. 대상 환자 군의 분포 및 특징

2017년 1월부터 12월까지 1년간 인하대병원 외래를 방문한 교정 4개월 미만인 462명 중 만삭아는 300명(64.9%), 임신나이 37주 미만으로 출생한 미숙아는 162명(35.1%)이었으며, 미숙아 중 임신나이 23주 이상에서 34주 미만으로 출생한 조기 미숙아는 72명(15.6%), 임신나이 34주 이상에서 37주 미만으로 출생한 후기 미숙아는 90명(19.5%)을 차지하였다. 교정 나이 4개월 미만의 외래 방문 3회까지의 자료를 수집하였는데, 당시 영아의 교정 연령 중앙값은 각각 21.7일(사분범위 0–46.1), 28.9일(사분범위 3.0–54.8), 42.7일(사분범위 19.7–65.7) 이었다.

2. 영아 산통의 발병률 및 위험인자

본 연구에서 정의한 기준에 따르면, 총 462명 중 167명이 영아 산통으로 진단되어, 36.1%의 유병률을 보였다. 영아 산통의 유병률은 성별에 따른 차이는 없었으며, 임신나이 39주 이상으로 출생한 영아에서는 23.3% (30/129)인 것에 반해, 임신나이 39주 미만으로 출생한 영아는 41.1% (137/333), 임신나이 38주 미만으로 출생한 영아는 47.9% (115/240), 임신나이 37주 미만으로 출생한 영아는 61.1% (99/162)로 미숙아에서 그 비율이 높았으며, 만삭아 중에서도 주 수에 따른 차이를 보여 어린 임신나이로 출생한 영아일수록 유병률이 높았다(P<0.001) (Table 2). 조기 미숙아는 75.0% (54/72), 후기 미숙아는 45.6% (41/90)로 미숙아 중에서도 조기 미숙아에서 그 비율이 높았다(P<0.001) (Table 2). 출생체중에 따른 비교에서, 출생체중 1.5 kg 미만으로 출생한 영아는 78.8% (26/33), 출생체중 1.5–2.0 kg에서 61.5% (24/39), 출생체중 2.0–2.5 kg에서 61.9% (39/63), 출생체중 2.5 kg 이상으로 출생한 영아는 23.4% (78/327)로, 출생체중이 작을수록 유병률이 높았다(P =0.002) (Table 2). 출생체중의 10백분위수로 나누어 비교하였을 때, 출생체중 10백분위수 미만의 부당 경량아(54.5% [30/55] vs. 33.7% [137/407], P =0.003)에서 유의하게 높은 빈도로 영아 산통이 발생하였다(Table 2). 수유 종류에 따른 비교에서는, 모유만 수유하는 경우 29.8% (25/84)로 영아 산통의 발생이 가장 적었고 모유와 분유를 혼합하는 경우는 32.8% (60/183), 분유만 수유하는 경우는 49.7% (77/155)의 유병률을 보여 수유 종류에 따른 유의한 차이를 보였다(P =0.001) (Table 2).

3. 영아 산통 증상의 발현 시기 및 특징

영아 산통 증상의 발현 시기는 월경 후 연령(postmenstrual age) 기준으로 조기 미숙아에서 39+5주(34+6–52+5), 후기 미숙아에서 39+4주(36+1–53+3), 만삭아에서 43+2주(39+0–57+5)로, 조기 미숙아와 후기 미숙아에서는 차이 없이 39주 후반에 증상이 발현하였으나, 만삭아에서는 생후 3주경 증상이 시작되었다(P<0.001).

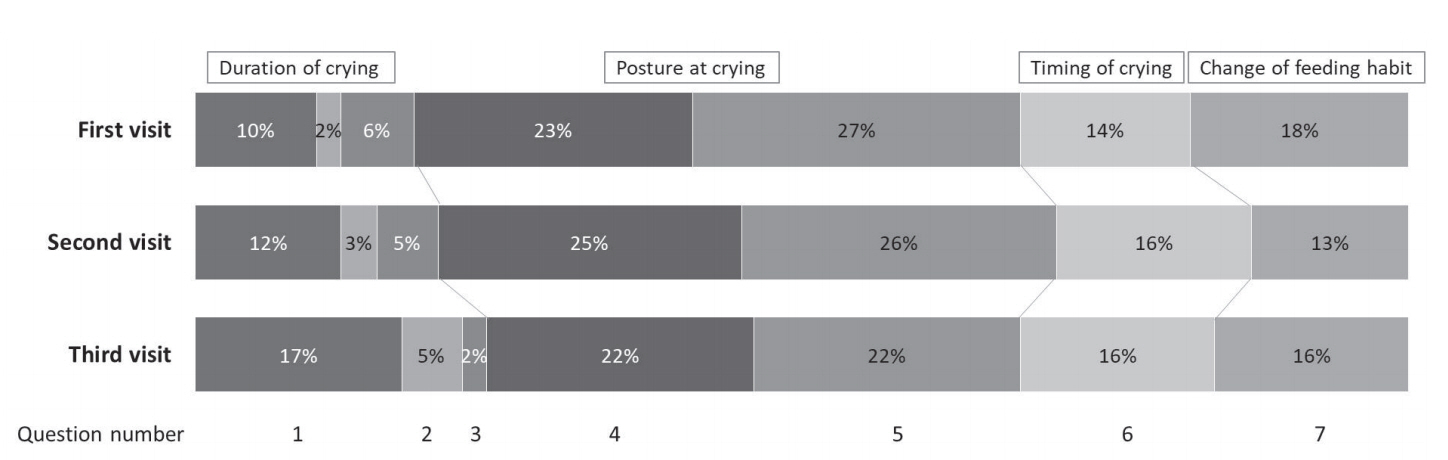

영아 산통으로 진단된 환아의 외래 방문 시 설문지 결과를 토대로 항목별 합산 점수로 보았을 때, 우는 동안 주먹을 꼭 쥐는 증상(설문 항목 6)이 보호자들이 가장 많이 호소하는 증상이었고(첫 번째 방문 27%; 두 번째 방문 26%; 세 번째 방문 22%), 우는 동안 등을 굽히거나 무릎을 배 쪽으로 굽히는 증상(설문 항목 4)이 그다음으로 많이 호소하는 증상이었다(첫 번째 방문 23%; 두 번째 방문 25%; 세 번째 방문 22%) (Figure 1). 심한 울음(설문 항목 1–3)은 외래 방문 초반에는 보호자가 크게 호소하는 증상이 아니지만(18%), 두 번째, 세 번째 방문째로 갈수록 심한 울음을 호소하는 비율이 증가하였다(두 번째 방문 20%, 세 번째 방문 24%) (Figure 1).

Composition of infantile colic symptoms. The most common symptom was clenching fists during crying, reported by 27%, 26%, and 22% of the participants at their first, second, and third visits, respectively. This was followed by the infants bending back or pulling their knees towards their stomach, observed by 23%, 25%, and 22% of the participants at their first, second, and third visits, respectively. Severe crying was not a major symptom at the first visit, but the second and third visits showed an increased rate of severe crying: 18%, 20%, and 24% at the first, second, and third visits, respectively. Question 1: Excessive crying lasting more than an hour a day; Question 2: Excessive crying lasting more than 3 hours a day; Question 3: Excessive crying lasting all day; Question 4: The baby bends back or pulls knees toward stomach whilst crying; Question 5: Excessive crying usually occurs in the afternoon or evening; Question 6: The baby clenches his or her fist whilst crying; Question 7: The baby eats less amount than usual in one feeding.

4. 영아 산통의 중재 및 경과

영아 산통으로 진단받은 167명의 환아 중 98명(58.7%)에서 저유당 분유(Novalac AC, United Pharmaceuticals SAS, Paris, France)로의 변경, 가수분해 분유(Absolute HA, Maeil Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea)로의 변경, galactosidase (Galantase Powder, Hyundae pharm, Seoul, Korea), Lactobacillus reuteri (American Type Culture Collection Strain 55730, 108 live bacteria per 5 drops, BioGaia AB, Stockholm, Sweden) 복용이 단독 혹은 복합으로 시도되었다. 시도된 중재 중 가장 많은 것은 저유당 분유로의 변경(71.4%, 70/98)이었으며, L. reuteri 복용(29.6%, 29/98), galactosidase 복용(9.2%, 9/98), 가수분해 분유로의 변경(8.2%, 8/98)이 그 뒤를 따랐다. 보호자가 호소하는 영아 산통의 주관적 호전 효과는 가수분해 분유로의 변경 시에 가장 좋았으며(87.5%, 7/8), 저유당 분유로의 변경(47.1%, 33/70), galactosidase 복용(44.4%, 7/9), L. reuteri 복용(34.5%, 10/29) 순으로 호전 효과를 보였다(Figure 2A). 또한 저유당 분유 변경을 단독으로 했을 때보다 저유당 분유와 L. reuteri 나 galactosidase의 복용을 함께 했을 때 더 좋은 효과를 보였다(47.1% vs. 69.2% vs. 100%, P<0.001) (Figure 2B).

Improvement effect of interventions. (A) The most improvement is observed with hydrolyzed formula (87.5%), followed by low-lactose formula (47.1%), galactosidase (44.4%), and the probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri (34.5%). (B) The combination of low-lactose formula with the probiotic L. reuteri (69.2%) or galactosidase (100%) shows better improvement compared to low-lactose formula alone (47.1%).

고찰

영아 산통은 주로 생후 4개월 이하의 건강해 보이는 영아에서 발작적인 보챔과 과도한 울음을 보이는 질환으로, 상당한 수의 영아와 보호자에게 고통을 안겨주며 치료하는 사람도 심각한 고민에 빠지게 한다. 지난 40년 동안의 많은 연구에도 불구하고 그 원인은 아직 명확하지 않은 상태이며, 여러 연구 결과를 통해, 이 질환이 미성숙한 위장관에서 기인하는 기질적인 통증에서 유래하는 것으로 추정되고 있을 뿐이다. 신생아가 통증을 인지하고 반응할 수 있을지에 대해 많은 논쟁이 있었지만, 통증 인지에 필요한 대부분의 해부학적 경로와 신경전달 물질의 기능이 이미 신생아기에 전부 혹은 거의 발달 되었다고 보고되고 있다[22,23]. 영아 산통의 유병률은 문헌마다 차이가 커서 적게는 10% 내외, 많게는 40%까지 보고되는데[24], Saavedra 등[25]에 따르면, 1,195명의 환아를 대상으로 한 코호트 연구에서 영아 산통을 호소하며 내원하는 영아는 80.1%에 육박하였으나, Wessel’s criteria에 합당한 기준을 만족하는 경우는 16.3%에 불과하였다. 또 다른 코호트 연구에서는 한 병원에서 출생한 모든 신생아를 3개월 동안 추적관찰 하여, Wessel’s criteria를 진단기준에 따랐을 때 영아 산통의 유병률은 각각 21.77%, 20.24%이었다[26,27].

본 연구에서는 인천의 큰 거점병원에서 신생아분과 전문의가 꾸준히 추적 관찰했던 영아들을 대상으로 하였다. 기존의 연구에서 시행된 1인의 의료진에 의한 진단보다는 의료진의 판단과 더불어, 보호자가 작성한 설문지의 최근 일주일 동안의 증상 일수를 기준으로 점수화하여 진단에 접근하였을 때, 본 연구에서의 영아 산통의 유병률은 36.1%이었다. 이는 이전에 보고된 유병률 중 높은 편에 속하나, 상세 불명의 발작적인 울음을 호소하는, 특이질환 없는 영아를 임상에서 흔하게 접하는 것을 고려해보았을 때, 상기 본 연구에서의 유병률은 의미 있다고 사료된다[24-27].

영아 산통의 위험인자나 원인은 아직 명확하게 밝혀지지 않았다. 미숙아, 저출생체중아에서 더 흔하게 발생하고[28,29], 분유 수유가 모유에 비해 영아 산통의 위험률을 증가시킨다는 보고도 있으나[25,30], 또 다른 연구에서는 임신나이, 출생체중, 수유 종류, 분만방법 중 어떤 것도 유병률과 유의한 상관관계가 있는 인자는 없다고 보고하였다[26,27]. 본 연구에서는, 영아 산통이 임신나이 37주 미만의 미숙아에서 만삭아보다 더 높은 비율로 발생하였고, 37주 이상의 만삭아 중에서도 39주 이상보다 37주나 38주로 출생한 영아에서 더 빈번하였고, 37주 미만의 미숙아 중에서도 후기 미숙아보다 조기 미숙아에서 그 비율이 더 높았다. 또한 10백분위수 미만의 체중으로 출생한 부당경량아에서 유의하게 높은 빈도로 발생하였고, 출생체중이 작을수록 더 높은 유병률을 보였다. 또한 모유에 비해 모유와 분유를 혼합하거나 분유만 수유하는 경우에 유의하게 빈번하였다.

문헌에서 영아 산통의 원인으로 제시되는 것들에는 유당(lactose) 흡수장애로 인한 과도한 복부 내 가스 발생, 장내 세균의 불균형, 위장관 미성숙, 세로토닌 과다 생성, 미숙한 보호자들의 수유 기술 등이 있으며, 4개월 미만의 영아에서 생리적인 유당분해효소(lactase) 불충분은 복부 가스 팽만을 유발하고, 이것이 영아 산통의 주요인이라는 의견이 가장 많다[31-34]. 저유당 분유(Novalac AC)는 유당의 함량을 일반 분유의 34.7%–37.3%까지 줄여 영아의 미숙한 유당 흡수력에 유리하도록 제조되었으며[35], 본 연구에서 유당이 없는 가수분해 분유(Absolute HA) 혹은, 저유당 분유(Novalac AC)로의 변경이나 galactosidase 복용이 영아 산통의 호전을 보인 것은 유당에 의한 가스 발생이 영아 산통의 주된 원인이 될 수 있음을 시사한다.

L. reuteri 균은 소화관에 정착하여, 면역세포(T림프구)를 증가시키는 것으로 확인되었고[36], 살균효과가 있는 항균물질인 reuterin을 분비하나, 그 생성량은 품종에 따라 다른 것으로 알려져 있으며, ATCC 55730 품종에서 눈에 띄게 많은 양이 생성되는 것으로 보고되고 있다[37]. 이와 같은 기전을 통해 L. reuteri의 투여는 괴사성 장염 예방 및 영아 산통의 증상 개선에 효과적이라는 것이 확인되었다[38]. 또한 다른 연구에서는 L. reuteri를 투여한 아이들이 Bifidobacterium lactis를 투여한 아이들에 비해 병원 방문, 어린이집 결석, 항생제 복용의 비율이 낮았음을 확인하였다[39]. 최근의 다른 연구에 따르면, 영아 산통으로 L. reuteri를 투여하였을 때 우는 시간이 1시간 미만 감소하여 영아 산통의 증상이 개선됨을 확인한바 있다[40]. 위 연구 결과들은 본 연구에서 L. reuteri의 복용이 영아 산통 증상의 호전 효과를 보인 것과 일맥상통하는 내용이다.

이번 연구는 단일기관의 후향적 연구라는 점과 3차 병원 신생아 분과 외래에 방문하는 환자를 대상으로 하여 미숙아가 차지하는 비율이 높기 때문에 이것이 선택 바이어스로 작용했을 가능성이 있다. 실제로 2011년도 통계청 자료에 따르면 임신나이 37주 미만의 출생아 비율은 6.0%이었던 반면에, 본 연구에서는 미숙아가 35.1% (162/462)로 높은 비율을 차지하였다. 또한 3차 병원이라는 특수성으로 인해 병원에 방문하는 부모의 경제적 여건, 사보험 유무 등이 병원 방문 비율에 영향을 미쳤을 것이므로 균일한 집단의 결론이라고 단정 지을 수 없다는 제한점이 있다. 유당 불내증이나 우유 알레르기, 항문 열상, 위식도 역류 질환, 변비 등 영아에게서 복통이나 통증을 일으킬 수 있는 다른 혼란변수에 대한 통제가 이루어지지 못했고, 본 연구에서 영아 산통 증상의 호전을 목적으로 시도했던 저유당 분유 혹은 가수분해 분유로의 변경, L. reuteri 복용, galactosidase 복용 등이 긍정적인 효과를 보였으나, 이는 대조군 없이 소수(98명)를 대상으로 시도한 결과로, 일반화시키는 데에는 무리가 있다. 또한 저출생체중아가 영아 산통 유병률이 높다는 결론은, 결국 미숙아군에서 유병률이 높다는 것과 겹칠 가능성이 존재하므로, 임신나이를 일원화시키는 매칭 과정이 필요하나 그럴 경우 대상군의 수가 너무 적어진다는 한계점으로 이번 연구에는 시도하지 못하였다.

4개월 미만의 영아 중 30%가 넘는 영아와 이를 돌보는 보호자들이 영아 산통으로 인해 고통받고 있음을 고려할 때, 금번 연구에서의 한계점을 보완하여 영아 산통의 원인 인자를 찾아내고, 적극적인 중재 방법을 모색하는 보다 체계적인 연구가 필요하다. 이를 통해, 영아 산통에 대한 평가와 중재에 대한 지침이 정립될 수 있을 것이다.

Notes

본 저자는 이 논문과 관련된 이해관계가 없음.

Acknowledgements

이 논문은 인하대병원의 지원에 의하여 연구되었습니다.